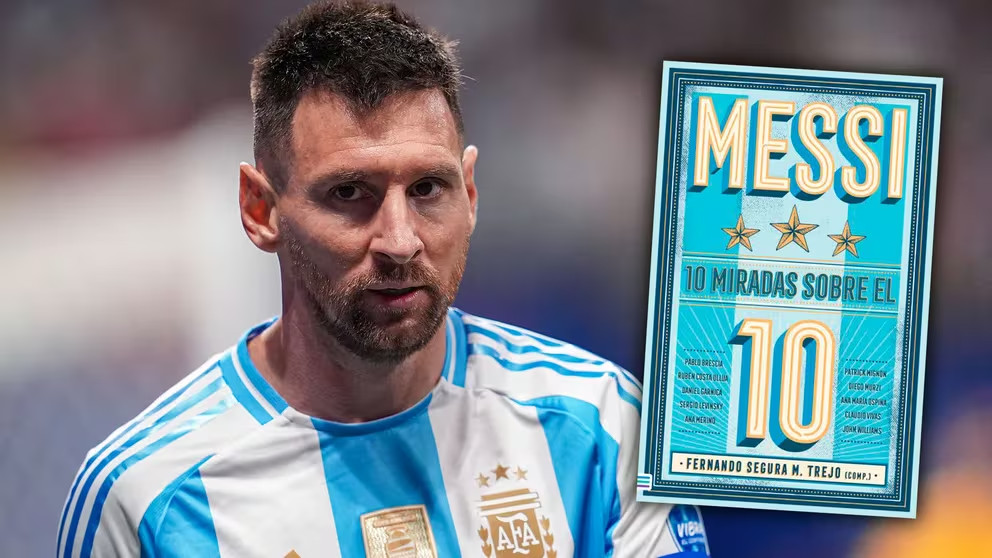

“Messi: 10 views on the 10” presents texts in perspective, from football and literature, about the life and work of the Rosario star, from Rosario to Qatar. Here, exclusively, a preview of the book

Lionel Messi is the central axis of the recent book Messi: 10 views on 10 , a volume that analyzes the career of the prominent Argentine soccer player through the eyes of different authors. The work, published by the Tendencias publishing house , brings together the observations of ten influential figures in the field of sports and literature.

The book traces Messi ‘s early days in his hometown of Rosario , through his time at FC Barcelona , his time at PSG , and his consecration at the World Cup in Qatar . This approach provides a multidimensional view of Messi ‘s career and his impact on both the sporting and symbolic spheres.

Among the authors are Fernando Williams , John Vivas and Claudio Garnica , who explore different aspects of Messi ‘s life . For example, Rubén Costa and Diego Murzi address Messi ‘s influence on a social and cultural level, while Sergio Levinsky and Pablo Brescia analyze his figure from a literary and media perspective.

Infobae Cultura shares a fragment of “The megastar who achieved a countercultural change in the Argentine national team”, Sergio Levinsky’s piece in that book.

The megastar who achieved a countercultural change in the Argentine team

Few might be interested that on August 17, 2005, the Argentine team beat its Hungarian counterpart 2-1 in a friendly match in Budapest with goals from Maximiliano Rodríguez and Gabriel Heinze. It sounds like that kind of commitments that become blurred over time, to the extent that official powers of greater importance overlap. However, there was a fact, contained in an event, that could have marked Argentine football in the 21st century, and that today can be told as a curious anecdote. And, for that to have happened, none other than Lionel Messi contributed with his character and his irrepressible decision.

In an attempt to give him space in the Argentine senior team, José Néstor Pekerman was very dedicated to observing the performance of the youth players, with whom he had won three U-20 World Cups, in 1995 in Qatar, in 1997 in Malaysia and in 2001 in Argentina, but which just over a year before the 2006 World Cup in Germany had taken on the responsibility of replacing Marcelo Bielsa – who argued that he had run out of “energy” after just over six years and with the classification on track – decided to give Messi a chance after his superb performance in Holland. In the U-20 World Cup that year, which had ended a month and a half earlier, exactly on July 2, the international promise of the National Team won the title of world champion with the team and the player of the tournament award.

And not only this. Before the final against Obi Mikel’s Nigeria in Utrecht, the contract renewal was signed with the Barcelona Football Club, whose leaders came to ensure that the young star signed with a termination clause that at the age of eighteen was equal to that of a consecrated teammate like the Brazilian Ronaldinho, in no less than one hundred and eighty million euros. Beyond the fact that his coach in that U-20 World Cup, Francisco “Pancho” Ferraro, had decided not to start him in the debut in the group stage against the United States – nor did Gustavo Oberman himself, when he saw himself on the board as a member of the initial team he was able to avoid the surprise—and that after winning the title he stated in the press conference after the final that if he had to highlight a player from the squad he would turn to the then midfielder Pablo Zabaleta, issues with which The Barcelona star would have to deal culturally for many years, it was evident that the eyes of many fans and the magnifying glass of much of the journalism were focused on Messi.

He was a young man who had not been seen in national competitions because he had emigrated to Catalonia when he was only twelve years old. Even so, if Messi was able to complete a brilliant journey in Holland that deserved a phone call and the first contact with the great Argentine idol, Diego Maradona, it was largely because after the defeat in the debut against the United States Ferraro had received another call, but much less flattering. It was the president of the AFA, Julio Grondona, to give him an ultimatum: either the Barcelona boy played in the U-20 World Cup or the coach returned to Argentina.

With the expectation of seeing him in action, although in a match without specific significance, Messi then entered against Hungary from the substitute bench eighteen minutes into the second half, with the number 18 on his back to replace the scorer Lisandro López. Just over thirty seconds had passed when he received the ball, he wanted to face his marker, Vilmos Vanczák, who crudely pulled on his shirt. The young Argentine shook him off with a slap that grazed his face. The home defender held his face. The German referee, Markus Merck, was carried away by this image and proceeded to directly expel the Argentine.

Only forty-five seconds had passed since his entry, with all the enthusiasm that could fit not only in him but in so many followers who thought they were in the presence of a different player, who came to generate light in complicated times, with meager results for the albiceleste. In the midst of so much disappointment, over the years, Messi confessed that, after what happened, he thought that the coach would never call him up to join the national team again. The curious thing is that in the images of the situation it can be seen that one of the teammates who argued most vigorously with the referee Merck was a certain Lionel Scaloni. Years later they met again in a different context and with an infinitely better outcome.

The story of Lionel Messi in the Argentine national team is, seen in retrospect, that of the triumph of talent, will, perseverance, resilience to overcome not only all kinds of criticism, many of them based on prejudices. For example, “leaving” parties when they seemed unfavorable, not being interested in your country because you live abroad, preferring money over a shirt, always wanting to impose your will by supposedly possessing absolute “power” when you already have it. He was an established star and, of course, there were conditions when the comparison with Diego Armando Maradona arose, to whom some press went so far as to pretend to ask permission to praise him, so that he would not feel that someone had appeared who could compare him.

It is, after all, the story of a countercultural winner because he achieved his greatest consensus when he seemed most depressed by the lack of results, for having reached the top without having even spent a season in soccer in his country, for having been contrasted, in his game and even in his life, with a demigod, and because he ended up being supported by a young generation in a country in which experience weighs when it comes to the impositions and decisions of the system.

The truth is that this little boy with straight hair, with very few words and a look towards the ground, of whom many Argentine journalists did not even know his full name and wanted to start a dialogue in Budapest to get to know him a little better, was growing so much in his club. , in Barcelona, who had won the title by beating the Frenchman Ludovic Giuly without breaking a sweat. His performance had been fundamental, with his talent and his speed, for his team to reach the final and win their second European Champions League at the end of that 2005-2006 season with the Dutchman Frank Rikjaard as coach. This, despite a very serious injury at Stamford Bridge against José Mourinho’s Chelsea in the round of 16 that caused him to leave crying uncontrollably and miss the final in Paris against Arsenal.

News

Messi break-up! Furious woman raffles off her boyfriend’s Copa America tickets and gives away his SIGNED Argentina shirt – after claiming he cheated on her with her best friend

A scorned woman has raffled her boyfriend’s Copa America tickets after he allegedly cheated on her – and even gave away his prized shirt signed by Lionel Messi. Candela Fassino decided to hit her boyfriend where it hurts the most – his love…

Mexico lost against Venezuela in the Copa América and the fans erupted with memes: “bipolar and loser”

Orbelín Pineda missed a penalty, the fans exploded against the performance of the Mexican team, they also criticized Jimmy Lozano On the second day of the Copa América , the Mexican team lost 1-0 against its counterpart from Venezuela . Although Jaime Lozano ‘s team dominated much of the match,…

Canelo Álvarez explains why he apologized to Lionel Messi after controversy at the Qatar 2022 World Cup

A year and a half after the controversy with Lionel Messi after Mexico’s defeat against Argentina in the 2022 Qatar World Cup, the boxer clarified in an interview why he publicly recanted A year and a half after the controversy…

What do specialists say about the discomfort that Lionel Messi suffered and what studies should be carried out in the coming days

The Argentine star played the 90 minutes of the victory against Chile, but, on repeated occasions, he was seen holding the back of his leg, especially the hamstring. Expert analysis of Infobae and the possible scenarios that await the captain…

How is Messi after the discomfort that scared everyone in Argentina’s victory against Chile: when would he play again

The captain will undergo studies in the next few hours, but there is optimism in the delegation regarding his recovery in the face of what is to come. The victory of the Argentine team against Chile meant their tenth match without losing in the Copa…

Argentina pending Messi who could miss first Copa América match since 2016

Miami (Florida), June 26 (EFE).- The Argentine team is pending the physical evolution of Leo Messi, who ended up last night with discomfort in his right adductor during the match against Chile and could miss the first Copa América match…

End of content

No more pages to load